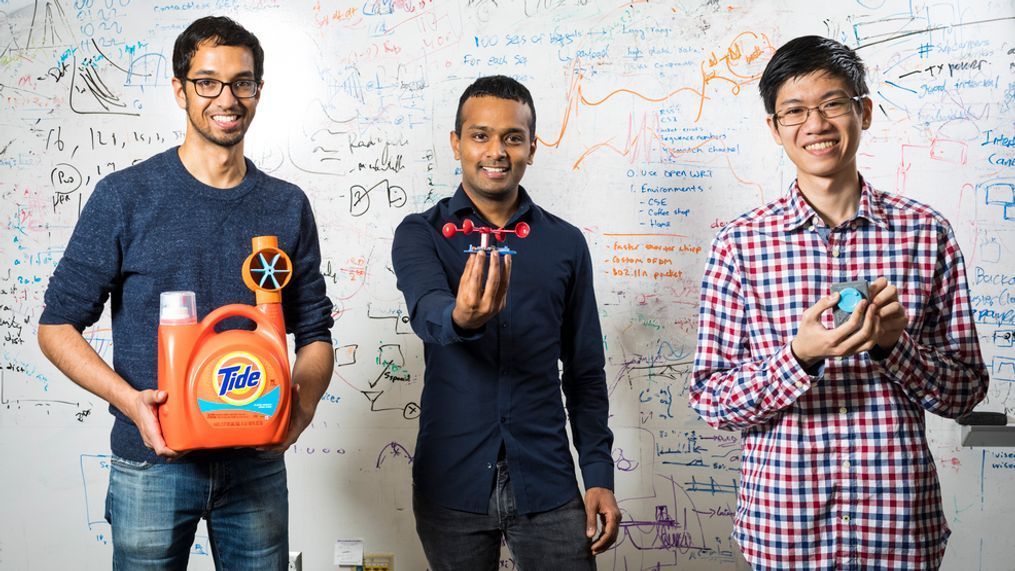

UW researchers pioneer way for ordering laundry detergent with 3D printing

SEATTLE -- There’s a new way to order laundry detergent, and it doesn’t involve shopping in-store or online.

Pioneered by the University of Washington, 3D printed objects can now do all the work for you, including monitoring your detergent use and placing an order the minute you’re running low. The main components: a cell phone, 3D printer, plastic-and-copper-filament, and a router.

“We were thinking about ways people can order things automatically, without pressing a button,” said Justin Chan, project team member from the Allen School’s Networks and Mobile Systems lab and UW Computer-science graduate student. “And what we’ve done is create something that can basically be stuck on top of a detergent bottle.”

As the laundry liquid is pouring out, the device attached to the detergent bottle, which includes plastic gears, springs, and a switch, tracks the speed of the flow and interfaces with the antenna. The speed at which the device is turning indicates how much soap is flowing out. If the speed dips below a certain amount, the antenna signal is picked up by your Wi-Fi router and sends the information to your Amazon app to order more.

“Let’s say you have a flashlight and you’re turning it on and off to send a Morse code,” said Vikram Iyer, team member and PhD. student in Electrical Engineering at the UW. “That’s something like your Wi-Fi router and phone are doing. The 3D objects are like mirrors reflecting or deflecting that bright light and using the antenna to send a message to a phone.”

The best part, it doesn’t take a scientist to carry out the procedure. The group’s designs are readily available online for free download and use. The hope was to see what the public would come up with.

As for the materials, both the antenna and switch, which are made using plastic-and-copper filament, are printed with a 3D printer and do not cost very much. The plastic material is about $30 and the 3D printer a couple hundred. A conductive filament for the antenna is also needed.

“There’s been a lot of interest in 3D printing,” said Iyer. “But a lot of these 3D objects have really complicated mechanical components and no way of interfacing with the electronic world. We wanted a way for objects to communicate with electronics.”

Now, six months later, they’ve accomplished just that.