Nissan workers in Mississippi begin voting on union

CANTON, Miss. (AP) — It's now up to workers at Nissan's Mississippi assembly plant to decide if they will be represented by the United Auto Workers union.

Voting began inside the plant at 2 a.m. Thursday in the election conducted by the National Labor Relations Board. Ballots can be cast until 7 p.m. Friday.

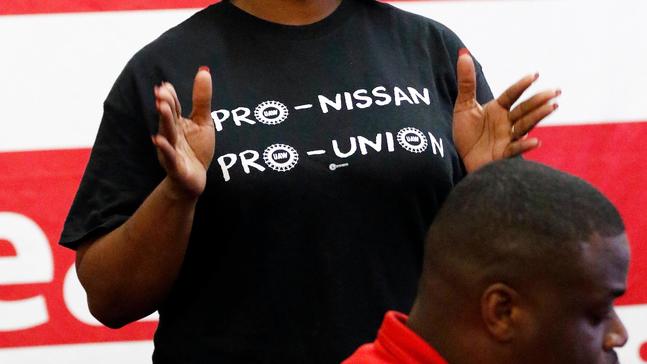

On one side are workers who say the 3,700 Nissan Motor Co. assembly and maintenance workers need a union to give them a voice in their workplace, to protect against arbitrary treatment, and to bargain for better benefits and pay.

Opposing them are other Nissan employees who reject the idea of a union speaking for them. They warn that the UAW would be an economic albatross burdening an employer who pays them well.

Outside analysts assume the union is an underdog, since the UAW has never fully organized a foreign-owned auto plant in the southern United States. But no one knows for sure.

"The vote will tell us the truth," said Bo Green, a Nissan worker who opposes the union.

So far, only maintenance workers at a Volkswagen AG plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, have been persuaded to join the UAW. But worldwide, the only Nissan factories without unions are the Canton plant and two plants in Tennessee.

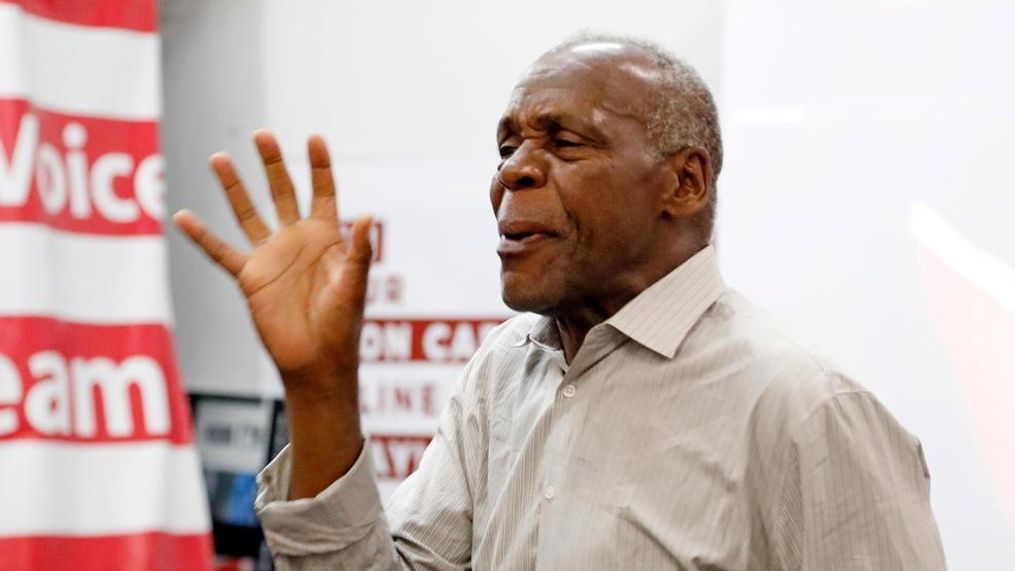

It's not an overstatement to say the world is watching — French politicians have been involved, and crowding into a sweaty union meeting Tuesday night were actor Danny Glover, a Brazilian unionist and a Japanese journalist.

About 6,400 people work for Nissan and its suppliers in Canton, where Frontier and Titan pickups, Murano SUVs and NV vans are assembled. But only direct employees can vote. Excluded are managers, engineers, clerical workers, guards, and hundreds of contract laborers who do the exact same work on the factory floor.

Union supporters say the UAW can prevent arbitrary treatment by managers and empower workers to bargain for better pay, working conditions and safety protections. They point to a worker in Mississippi who lost several fingers on an assembly line, and another in Tennessee who was killed on the job.

Foreign automakers came to these states in part to avoid unions and keep wages low. Mississippi, for its part, granted the Japanese-based company subsidies and tax breaks that could be worth more than $1 billion over 30 years.

As Senate Majority Leader, Mississippi Republican Trent Lott promised that Nissan would "revolutionize" the state's economy, and Mississippi's business and political leaders still mostly line up against the union. Republican Gov. Phil Bryant calls UAW supporters "socialists."

"I don't think we need a union to come in there and tell us how to make a better automobile," Bryant said during a speech last week. "They can get back on the Bernie Sanders bus and go back to New York, and I'll pay their way."

The independent senator from Vermont and many of Mississippi's African-American politicians back the UAW, which spent years cultivating ministers and other local leaders. With the Canton plant's majority African American workforce in mind, the union has promoted historic ties between the labor and civil rights movements. In response, Nissan has saturated local television with campaign-style ads and posted "vote no" signs along roads for miles around.

"It's kind of brutal, the constant bombardment of 'The UAW is the most terrible thing ever,'" said union supporter Earnest Whitfield, who works with machines that stamp steel into parts for the cars and trucks.

UAW Secretary-Treasurer Gary Casteel accuses Nissan of breaking federal labor law by pressuring workers to vote "no," and the NLRB has alleged eight violations of federal law. Rodney Francis, the plant's human resources director, told The Associated Press on Monday that Nissan is merely trying to dispel the union's "false promises."

It's illegal for managers to threaten layoffs ahead of a union election. Nissan has turned the argument around, blaming the UAW for the troubles of General Motors, Ford and Chrysler over the years.

"Look at the UAW's record on strikes and plant closing and layoffs," Francis said. "Unions make the company less able to be flexible and to meet the market demand."

Green, the union opponent, sees the plant closing if the UAW gets in. He says three relatives lost jobs when GM closed its plant in Shreveport, Louisiana, but Nissan has never laid off a direct employee.

"You've got one company that's doing good. They don't got the UAW," said Green. "You've got another company that's doing poorly. They've got the UAW."

Analysts say Nissan won't likely abandon a $3.3 billion investment in the plant, which has an annual capacity of 450,000 vehicles, about 8 percent of Nissan's worldwide production. And union supporters say management is to blame for the historic downturns of the Detroit Three.

"All of a sudden, if we have a union, is management going to stop managing the way they have in the past?" Whitfield asked.

![Image for story: 2020 Hyundai Sonata: Upping the ante on midsize sedans [First Look]](/resources/media2/16x9/full/360/center/80/0757332b-e97b-480c-9b65-b974626ec93e-large16x9_2020HyundaiSonataLimited29.jpg)