Shrinking water levels at large US reservoir reveal natural wonders hidden for decades

Eric Balken calls Glen Canyon "America’s lost national park."

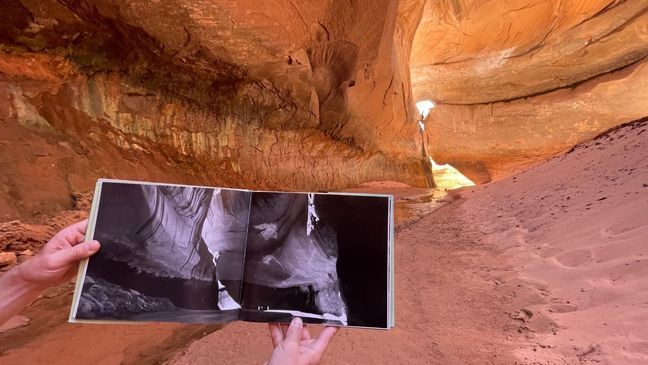

“There’s nowhere else like this,” he said while taking KUTV to see one of the area’s premier attractions.

“Cathedral in the Desert was one of the crown jewels of Glen Canyon,” said Balken. “It’s one of the iconic landmarks of this place.”

Walking into Cathedral in the Desert is likely to be an awe-inspiring moment for anyone. Think of it like a giant slot canyon. But instead of being narrow from top to bottom, it opens into a giant cavern on the canyon floor. A gentle waterfall spills over a sandstone shelf into a small, tranquil pool. It can be described as a hushed, hallowed space that can easily remind you of a man-made cathedral.

“I’ve probably been into Cathedral 25 or 30 times now,” said Balken. “It never gets old.”

Cathedral in the Desert, and other natural wonders throughout Glen Canyon, were never supposed to be seen again. Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1963. Water from the Colorado River then began to back up behind the dam. Over the course of 16 years, as the newly formed Lake Powell rose higher and higher, these natural wonders slipped below the waves.

Lake Powell isthe second-largest artificial reservoir in the U.S., following behind Lake Mead. It's located on the Colorado River and spans two states – Utah and Arizona,

“For many years, we wondered if we’d ever have the opportunity to actually walk into Cathedral in the Desert again,” said Balken.

Balken is executive director of the Glen Canyon Institute, a non-profit with the mission of restoring Glen Canyon and a free-flowing Colorado River through the Grand Canyon.

Restoring Glen Canyon, and what that would mean for the dam and Lake Powell, is a story for another time. Rest assured, it’s an issue with huge political, economic, environmental and energy implications.

But on this trip, KUTV simply asked Balken to show what’s reappearing in Glen Canyon after being underwater for decades.

“Cathedral in the Desert is definitely one of the most well-known landmarks in Glen Canyon but there are waterfalls and alcoves and places all over Glen Canyon that were inundated when the dam was built,” said Balken.

These places are being revealed because of record-breaking drought across the American West. As of early July, Lake Powell is only at about 25% of its water storage capacity. Water levels have gotten so low that these once-submerged natural features can be seen again in many places.

“Gregory Natural Bridge is one of the largest natural bridges in the country,” said Balken, showing another reappearing natural wonder. It’s just as impressive as other natural arches and bridges that draw millions of tourists to Utah. But unlike Delicate Arch and Rainbow Bridge, it’s been completely hidden until now.

“The top of it was inundated in 1969 and it was revealed for the first time, since then, last summer,” said Balken.

When once-flooded canyons and side canyons are exposed, there are scars from being underwater for so long. Lake Powell’s infamous "bathtub ring" is perhaps the most well-known example. But Balken said that ring is disappearing rather quickly in many places.

“The bathtub ring that we see is a calcium deposit on the rock,” he said. “If it’s in an area where water runs over it, it actually gets washed away over time.”

Balken showed KUTV one area in Lake Powell’s main channel where the ring is very faint.

“You can see the upper part of this wall right here that’s been out of water for probably over 10 years, maybe 20 years,” he said. “You can hardly tell the bathtub ring was ever there.”

While the bathtub ring may slowly fade, another impact from the reservoir can actually disappear quicker than scientists imagined.

“How long ago was it that where we’re standing now we would be under piles of sediment?” KUTV'sLincoln Graves asked Balken, as the pair stood in a dry upper portion of Fiftymile Canyon.

“We would probably be under sediment at this time last year,” he responded.

All rivers naturally carry huge piles of sediment downstream. But when a dam is built, that sediment just piles up on the reservoir floor. As water levels in Lake Powell have dropped, those sediment piles can easily be seen. But Balken also said they are easily washed away during monsoonal flash floods.

“We’re seeing this happen in every side canyon,” he said. “There’s a lot of moving sediment in here, there’s a lot of change happening. There’s a lot of ecological restoration.”

A giant pile of sediment could also be seen in Cathedral in the Desert in early July 2022. Even that is getting scoured out at regular intervals.

“We’re seeing this waterfall now restoring to almost what it looked like before the dam was put in,” said Balken. “So, in Cathedral in the Desert, we’re seeing restoration happen really quickly, faster than a lot of people thought was possible.”

Back in Fiftymile Canyon, Balken said plant life is also coming back quickly. As visitors hike farther up the canyon, they'll reach the old high point of Lake Powell.

“This has been out of the water for over 20 years now,” he said. “This is a really good example of the environmental restorations that happen in these canyons.” A person touring the area can see tall cottonwood trees and full willow groves. Balken calls it a thriving desert ecosystem. “It’s really hard to tell there was ever a reservoir here,” he said.

If Lake Powell continues to shrink, Balken said he’s confident more natural wonders will continue to emerge.

“There are endless alcoves, waterfalls, grottos and glens here that have yet to be seen,” he said. “There’s probably an endless amount to be discovered in Glen Canyon as this reservoir retreats.

A reversal in drought conditions could easily lead to Cathedral in the Desert, and other attractions, being inundated once again. But Balken believes the long-term trend is clear in the American southwest.

“The disappearance of this reservoir is a function of overconsumption of water accelerated by climate change,” he said. “It’s pretty simple math, right? The Colorado basin is using more water than naturally flows in the river. The main reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, they were built to catch excess water and there is no more excess water.”

Whether he’s right or wrong, he’s still advocating for people to come and see what’s being revealed by lowering reservoir levels.

“We’re seeing Glen Canyon come back to life before our eyes,” said Balken. “Which is really an incredible thing to witness in person. It’s a generational opportunity. It’s important that we take stock of the resources emerging in Glen Canyon and understand their value.”