From Founding Fathers to today: A look at 9 eclipses over the past three centuries

WASHINGTON (Sinclair Broadcast Group) - From the founding of the United States to the current century, solar eclipses have inspired awe and public fascination, marked turning points in U.S. history and have been a cause for scientific curiosity, discovery and advancement.

The August 21 Great American Eclipse will be the first time in nearly 100 years that a total solar eclipse will be visible from coast to coast across the United States, but not the first time Americans have looked to the skies to change the world around them.

“A total eclipse is a rare and spectacular event, one that transcends politics and plucks us out of our everyday lives,” author and umbraphile David Baron told Sinclair Broadcast Group. “It’s a humbling reminder of our place in the cosmos, that we are tiny beings at the mercy of forces so much larger than any of us."

"A total eclipse is a chance to appreciate the wonder and beauty of the universe.”

What follows are the historical, scientific and cultural highlights from America's great solar eclipses.

ECLIPSES OF THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR

JUNE 24, 1778 - GEORGE WASHINGTON’S ECLIPSE

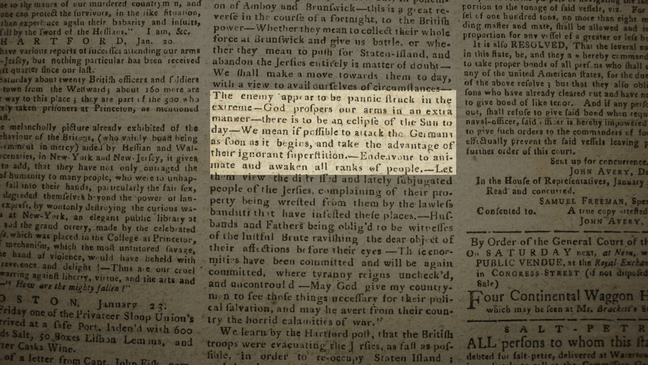

On the day of the eclipse, General George Washington was reportedly holding a war council in Hopewell, New Jersey. Prior to the eclipse, Washington had sent word to his commanders in the Continental Army, alerting them to coming phenomenon and preempting the fears and apprehensions of the soldiers.

George Rogers Clark, officer in the Virginia militia, reportedly used the eclipse to his advantage, telling his men that it was a good omen. Less than two weeks later on July 4, Clark and his men captured the city of Kasakia in one of the Revolution's westernmost campaigns.

For years after, the eclipse would be remembered as portending victory for the Continental Army in the Battle of Monmouth, which took place two days after the eclipse.

One week before the forecast date, British soldiers occupying Philadelphia left the city on news that the French has just entered the war.

This was good timing for David Rittenhouse, an astronomer, mathematician, mechanic and celebrated member of the American Philosophical Society living in Philadelphia.

According to records, Rittenhouse observed the eclipse along with Dr. William Smith, but records of their notes are scant.

Fellow member of the Philosophical Society and future President Thomas Jefferson was even closer to the direct pathway of the eclipse which traversed the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies. In a dispatch to Rittenhouse, Jefferson lamented, "we were much disappointed in Virginia generally on the day of the great eclipse, which proved to be cloudy."

Wartime conditions stressed the resources of the fledgling United States, which could account for the lack of observations.

One tremendous account has survived and was written in the North-Carolina Weekly Gazette on June 26.

The eclipse, which was visible on account of "tolerably clear" weather, "was observed with great attention, and some surprise to the ignorant," the paper reported.

"This was the greatest eclipse of the sun ever seen here by the oldest people now living among us, and exhibited a scene truly awful," the paper reported.

"The gradual obscurity of the sun, the decrease of her light, the sickly face of nature, and at last the total darkness which ensued, the stars appearing as at midnight, and the fouls seeking for their nightly shelter, caused a solemnity truly great."

OCTOBER 27, 1780 - ECLIPSE EXPEDITION PREVAILS AMID WAR

Perhaps even more dramatic, were the conditions under which the second total solar eclipse of the Revolutionary War was observed.

Having missed the great scientific opportunity of the previous eclipse, scientists and statesmen in Massachusetts prepared to seize on the 1780 eclipse "to prove the new state of the new nation was capable of mounting a scientific expedition on its own initiative," wrote historian Robert Rothschild.

Harvard Professor Samuel Williams helped convene the team of scientists for the expedition to Penobscot Bay in Maine, a location Williams calculated as most ideal for observing the total solar eclipse.

Five years into the war, James Bowdoin, founder of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, appealed to the Massachusetts legislature to outfit the group with supplies.

He wrote emphatically listing the causes for the mission: "That he cannot find that any total Eclipse of the sun has ever been seen here from the first Settlement of the Country, nor will any such be visible here until the year 1806; That the observations of Eclipses have been attended with so many advantages to mankind that they are universally esteemed object of Great Attention in every Civilized Nation."

Williams turned to the Board of War, which oversaw the entire Continental Army, requesting the use of a ship, the Lincoln galley, to bring the team to the observation site.

The petitions were granted and negotiations with the British forces were successful in guaranteeing safe passage for the expedition.

In a later account of the expedition, Wililams wrote, "Though involved in all the calamities and distresses of a severe war, the government discovered all the attention and readiness to promote the cause of science, which could have been expected in the most peaceable and prosperous times; and passed a resolve, directing the Board of War to fit out the Lincoln galley to convey me to Penobscot."

Ultimately, Williams' calculations were flawed. The location was off and he missed totality. However, what he observed was a phenomenon, Baily's Beads, that was a scientific mystery until 1838.

"The sun’s limb became so small as to appear like a circular thread or rather like a very fine horn," he wrote.

"Both the ends lost their acuteness and seemed to break off in the form of small drops or stars some of which were round others of an oblong figure. They would separate for a small distance, some would appear to run together again and then diminish until the whole disappeared."

The expedition was a proof of concept of something that would become typical in the American experience, namely, institutions of science, government, academia and the military collaborating to further scientific and technological progress.

=======

ECLIPSES OF THE 1800s

JUNE 16, 1806 - THE GRADUAL APPROACH OF DARKNESS

The June 16, 1806 annular eclipse traversed the country from an area just south of San Diego through New York and New England.

“So rare a phenomenon has not happened since the settlement of this country,” the National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser reported days beforehand. “Indeed, we recollect not to have read of but one instance of the kind.”

Following the eclipse, the same paper detailed the event as viewed from New York: “The gradual approach of darkness, the pale and sickly hue given to the objects around us, the brilliant appearance of a few stars, the general suspension of business, the streets lined with inhabitants, all anxiously viewing the appearance and the progress of this sublime phenomenon, and the recollection that many generations must pass away before so grand an exhibition of the kind will occur, all conspired to produce an effect on the mind which cannot be described.”

Prior to the eclipse, Andrew Newell of Boston published a pamphlet titled, “Darkness at Noon, or the Great Solar Eclipse of the 16th of June, 1806, described and represented in every particular, containing, also, a general explanation of eclipses and the causes on which they depend.”

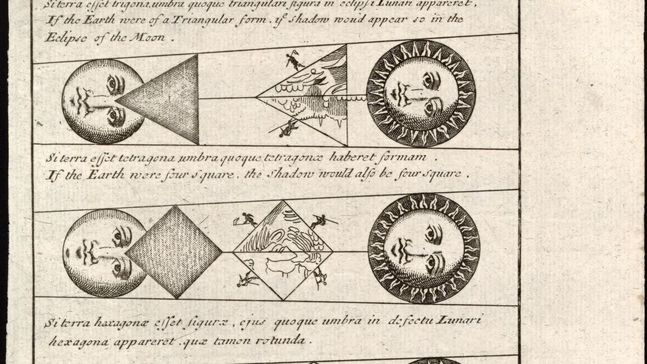

“In the less enlightened ages of the world, the eclipses of the sun and moon were regarded with surprise and consternation, and as intimations of divine displeasure. Amongst many of the ancients, they were considered as the harbingers of disastrous events, and as indications of some revolution in the physical system of things.”

In a letter that fall, President Thomas Jefferson lamented that he was unable to get a better view of the eclipse.

“Fortune seems to have favored every other place but this with a fair view of it,” Jefferson wrote to surveyor Andrew Ellicott, who had sent along his observations. “This spot was covered by a dense cloud through the whole of its duration, & for some time before & after. I hope the great extent of the path of this eclipse round the globe, & especially thro’ our states will furnish many useful corrections of our longitudes. Capt. Lewis will bring us a treasure in this way.”

MAY 26, 1854 - PICS OR IT DIDN'T HAPPEN

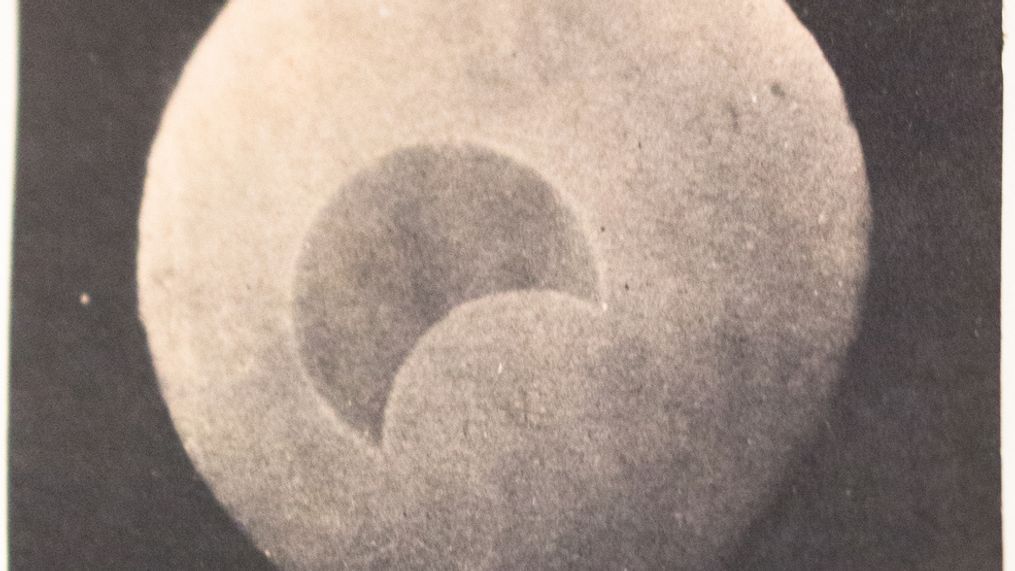

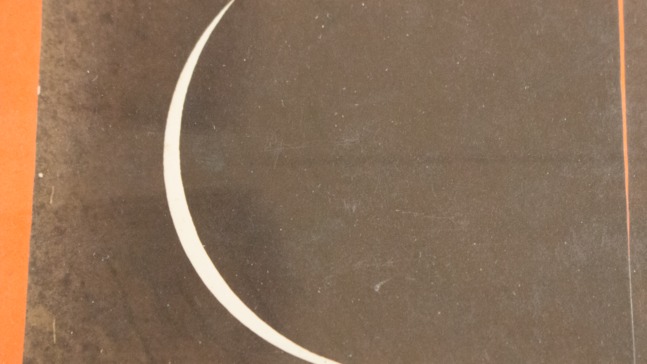

A May 26, 1854 total eclipse only passed directly over parts of the northwest and northeast of the U.S. and several provinces of Canada, but it was noteworthy for being the first such event visible in North America after the invention of the daguerreotype, the first publicly available photographic process. Seven images taken by William and Frederick Langenheim have survived, as have a few taken by other photographers.

In an article published on the morning of May 26, the New York Herald attempted to prepare readers for viewing the event by, among other things, recalling other eclipses throughout history.

“But the greatest eclipse of which we have any record is that which occurred at the death of our Saviour,” it states. “‘And it was about the sixth hour,’ says the inspired writer, ‘and there was a darkness over all the earth until the ninth hour, and the sun was darkened.’ This was a general eclipse, a total darkness having fallen upon the earth for three hours.”

The Herald also informs readers of the superstitious beliefs of “the Orientals” about eclipses:

“The Orientals, generally, looked upon eclipses as occurrences of a supernatural character, and attributed them to magical science, or evil demons who were endeavoring to destroy the luminary. In fact, they considered it a struggle between the powers of good and evil, and they awaited the issue with breathless anxiety, trembling with apprehension as the shadow passed over the disc of the sun, and radiant with joy and triumph as it receded and ultimately disappeared. Some more zealous or more courageous than the frightened multitude, formed themselves into volunteer auxiliary corps to assist the sorepressed (?) God of Day, and armed with gongs and kettle drums endeavored to drive away his terrible enemy.”

The following day, the Daily Union of Washington, D.C. struggled to relate the experience of the eclipse to its readers.

“Lamentably deficient ourself in the science of astronomy, we cannot, with instruction or interest to the reader, dwell upon the imposing phenomenon but will only say that, in all respects the scene equaled in magnitude and interest in the expectation of our citizens,” they wrote before simply quoting the “Encyclopedia Americana” entry on eclipses.

JULY 29, 1878 - THE AMERICAN ECLIPSE

The path of totality for the eclipse of July 29, 1878 passed over Alaska before traveling over the continental U.S. from Montana to Louisiana—“from Siberia to St. Domingo,” as the New York Herald put it.

Astronomers saw a great opportunity to learn from the eclipse, and apparently some in Washington did too. Congress appropriated $8,000 for scientific expeditions to the Rocky Mountains to witness the event.

The day before, the Herald published an extensive guide for viewing the event “so that the popular interest in the event may be based on an intelligent appreciation of all the facts relating to it.” The Rocky Mountain News offered similar but more concise directions, which it described as “a good thing to cut out and paste in your bonnet.”

On July 30, the Herald ran a report via telegraph from Wyoming, where Thomas Edison and others were stationed.

“The observation of the eclipse has been a grand success and the astronomers here are in a high state of happiness. Everything passed off in the most satisfactory manner.”

According to David Baron, author of “American Eclipse: A Nation's Epic Race to Catch the Shadow of the Moon and Win the Glory of the World,” the 1878 eclipse was important for a number of reasons, not the least of which was that it was passing directly over the country’s burgeoning western frontier. This offered Americans a valuable opportunity to study the still-unsolved mysteries of the sun.

“In 1878, the U.S. was a young country with a poor reputation in the sciences," he said. "The eclipse offered American scientists a chance to show Europe that we were an intellectual force to be reckoned with. It was a chance for the country to prove that it was a player on the international, scientific stage.”

From a scientific perspective, though, the biggest developments resulting from the eclipse were underwhelming. Astronomer James Craig Watson was seeking evidence of a planet called Vulcan orbiting somewhere between Mercury and the sun. Edison was testing a new invention called a tasimeter that was intended to detect heat in the sun’s corona.

“Obviously, neither of those announcements withstood the test of time,” Baron said. “There is no planet Vulcan, and Edison’s tasimeter turned out to be a dud—forgotten in the dustbin of history.”

Instead, Baron said the lasting impact of the 1878 eclipse was social.

“The eclipse inspired America to rally around science as a shared, national goal—sort of like the moon landing would be a century later,” he said. “It was an important step toward the United States becoming, in the twentieth century, the world’s scientific superpower.”

=======

Turn of the 20th Century

At the turn of the 20th century, scientists were making significant advancements in eclipse study.

JUNE 8, 1918 - THE SOLAR ECLIPSE OF WORLD WAR I

Albert Einstein published his Theory of General Relativity in 1915. He proposed “that gravity is not an actual force, but is instead a geometric distortion of space-time not predicted by ordinary Newtonian physics,” according to NASA. The greater the mass and gravitational pull, the greater distortion. This would apply to all objects moving through space in a vacuum, including rays of light.

To understand if this distortion occurs during an eclipse, measurements are needed of the star placements around the sun before, during and after the eclipse takes place. Because the sky does not always completely darken, this made Einstein theory difficult to test during solar eclipses more than a century ago.On June 8, 1918, a total solar eclipse stretched across the country from Washington to Flordia.

But it was the following year in 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington, a British physicist, attempted to test Einstein’s theory by measuring the placement of stars by taking photographs during a solar eclipse.

SEPTEMBER 10, 1923 - NEWSPAPERS HIGHLIGHT LINGERING QUESTIONS OF SOLAR ECLIPSES

“The curvature of such threads is being carefully studied with the view of learning more about the magnetism of the sun,” one report wrote in the Washington Evening Star newspaper.

After the Sept. 10, 1923, solar eclipse, Manger White of the San Diego Sun, won the 1924 Pulitzer Prize for vividly reporting on the celestial event. The Washington Evening Star newspaper, which ended circulation in 1981, wrote about the questions scientists still had regarding the study of eclipses.

“The sun rotates in about twenty-five days. Does the Corona rotate with it? We are trying to find out. The corona contains a substance or substances unknown on the earth,” the newspaper wrote.

We now know that sun rotates on its axis “in about 27 days,” according to NASA. The solar rotation itself varies by latitude; meaning the corona won’t change much when we observe the eclipse Aug. 21. We also know that the sun is mostly made up of Hydrogen gas in the form of plasma.

Ivona Cetinic, NASA scientist with the Universities Space Research Association, said that by studying the sun we gain a greater understanding of life on earth.

“It starts off with this little plant like organisms that use solar energy to convert inorganic lifeless carbon into life form and also produce oxygen that we breathe. So, it is really crucial for us to understand the impact of sun on our climate but also life on earth,” Cetinic said.

She added that the discoveries and advancements made in the study of the sun and eclipses within the last hundred years have grown from the discoveries that proceeded them in a synergistic relationship.

“Each of these advances steps on top of each other and opens up a new way and a new door and brings a new dimension to our knowledge,” Cetinic said.

FEBRUARY 26, 1979 - THE LAST CONTIGUOUS SOLAR ECLIPSE

The last contiguous solar eclipse, meaning the eclipse crossed over states that bordered each other, was Feb. 26, 1979. The line of totality entered the United States between Washington and Oregon then traveled up into Canada. ABC News issued a special live report of the event on television.

As the eclipse neared the point of full totality over Oregon, the anchor described the scene as “midnight in Portland.”

As the eclipse reached totality, crowds off camera could be heard cheering.

When the event reached its conclusion, anchor Frank Reynolds signed off saying “not until Aug. 21, 2017, will another eclipse be visible from North America, that’s 38 years from now. May the shadow of the moon fall on a world at peace.”