'We've seen this movie before': 2024 shapes up to be a rematch

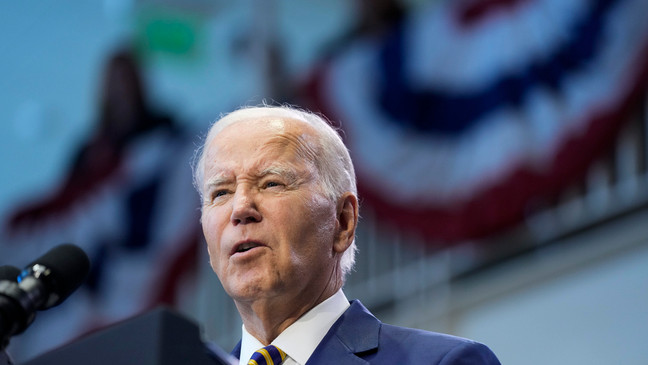

HUNT VALLEY, Md. (TND) — This year’s presidential election is shaping up to be the rematch of two historically unpopular presidents, the rematch that nobody wants, but somehow is likely still happening: Joe Biden versus Donald Trump.

Both men have lived in the same house on 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Both have addressed the nation from the same Oval Office; both have been chosen by American voters as the best person to be the face of the country, and one of the most powerful people in the world.

Yet, roughly half of Americans heavily dislike one or the other. Just 4% of Republicans view President Biden favorably, and just 6% of Democrats view former President Trump favorably, according to the latest Gallup polling.

A solid majority of Americans, 67%, say they’re “tired of seeing the same candidates in presidential elections and want someone new,” according to a new Reuters/Ipsos poll.

Eighteen percent say if it is, indeed, a rematch, they just won’t vote at all.

Both candidates are 77+ years of age, and both could only serve for four years if elected this November.

Those ingrained in the world of politics often say presidential elections are referendums on the incumbent. This election may, instead, be a referendum on both, but voters may have to pick one.

With Trump and Biden maintaining significant leads over their rivals as primaries kick off, it’s hard to imagine 2024 being all that different from 2020. Plus, voters already know who the candidates are, and how they govern.

So far, Biden’s messaging has, in some ways, reflected his messaging in 2020: “Look at Trump. I’m not him. Vote for me!”

His campaign has dubbed Trump as a “wannabe dictator,” a “threat to democracy” and a candidate running solely for “revenge and retribution.” The Jan. 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol is a focal point, and Trump’s mountain of legal troubles supplements it.

While the strategy may have played a factor in his 2020 victory, some experts think it may not change much this go-around.

“It may appeal to Joe Biden’s base, but I think that base already feels that way, and there’s no real room to grow that number,” said W. Joseph Campbell, professor emeritus of communication at American University in Washington, D.C.

Aside from that approach, the Biden campaign is propping up the president as the candidate who will protect reproductive rights and the climate. Biden points to slowing inflation as proof his economic policies are working.

Meanwhile, Trump is using his four criminal indictments and 91 felony charges to what appears to be his advantage. He claims Biden’s Justice Department and the FBI are being weaponized against him while being soft on Biden’s allies and his own family members.

The former president is also targeting Biden’s policies on the economy, immigration and foreign affairs.

But, Campbell points out, Trump is still replaying 2020 and claiming the election was stolen from him, which may be getting old.

“There’s a lot Trump could be focusing on, but I think he tends to focus on stuff that is very personal to him and his personal grievances, which get to be boring and in the way, and don’t really have the effect of persuading independent voters.”

Trump has never carried more than 45% of the popular vote, so Campbell says he’s “pretty clearly got to win more than just the Republican base to win the election in 2024.”

However, in today’s increasingly polarized day and age, winning over members of the other major political party seems like an uphill battle.

Since Trump’s election in 2016, the share of Democrats who view Republicans as “immoral” has surged – from 35% to 63%, according to the Pew Research Center. The number of Republicans who feel that way about Democrats surged from 47% to 72%.

More than six decades ago, according to YouGov, just 4% of Americans said they’d be displeased if their child married someone from the other party. That share jumped to nearly 40% in 2020.

Today, only about 4% of all marriages are between a Republican and Democrat.

As this New York Times analysis points out, both parties essentially interpret reality differently.

Take Trump’s indictments for example: one party tends to view them as legitimate, concerning and disqualifying for someone vying for the White House; the other views them as borne out of corruption and entirely political.

Take the 2020 election: one party thinks Trump lost fair and square; the other thinks it was stolen through a coordinated effort by the government.

Take the Jan. 6 Capitol riot: one party calls it an “insurrection,” an attempted hostile takeover of the government that resulted in fatalities; the other believes it was an inside job by the FBI, or a mostly peaceful show of support.

With such far-apart realities, can any message or argument pull someone over from the other side?

“We’ve seen this movie so many times before, including with these exact two candidates, where it just seems like voters' minds are so made up that whatever is the exciting story of the week doesn’t seem to change the minds of the average American.”

David Broockman is an associate professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley, and the director of the Berkeley Center for American Democracy.

The way he sees it, it may not even matter what messaging the Biden and Trump campaigns go with – everyone already knows where they stand. This could also explain why, despite very little enthusiasm or popularity surrounding either candidate, they’re the ones winning again.

“People’s exhaustion reflects the fact that they know so much,” Broockman said. “But the fact that people know so much also makes persuasion really hard because people know how they feel about these candidates.”

Furthermore, Broockman posed the question: Is it even possible to predict what political messaging will work? Negative attack ads may work one year but not the next; highlighting a candidates’ background or skeletons in their closet may work one year but not the next; testimonials may really resonate with voters one year, but not the next.

He pointed to a study he helped author that found “political practitioners and laypeople both perform barely better than chance at predicting persuasive effects.”

In other words, when they surveyed campaign consultants and had them predict whether a political message would benefit the candidate, they were only slightly better than flipping a coin.

“I don’t think that reflects that they’re stupid or they’re bad at their jobs,” he said. “It just reflects the fundamental nature of this messaging question, which is that it’s extremely hard to predict such a complex phenomena, when you actually really need the real time data to understand what’s resonating with voters.”

Not to mention, the last time the U.S. saw two people who had already been president before run against each other again was more than 130 years ago. Democrat Grover Cleveland defeated Republican incumbent Benjamin Harrison, becoming the first former president to be voted back in.

But, it’s not like Cleveland faced potential criminal convictions and prison sentences.

“This is like a mind-altering set of circumstances, and just how that’ll play out is unclear,” Campbell said. “It’s uncharted territory.”